1893 -1900

Charcot (1893)

From October 1885 to February 1886 Freud worked at the Salpetriere in Paris under Charcot. This was the turning point in Freud’s career, for during this period his interest shifted from neuropathology to psychopathology, from physical science to psychology. The obituary, written only a few days after Charcot’s death, is some evidence of the greatness of Freud’s admiration for him. Charcot treated hysteria as just another topic in neuropathology. He gave a complete description of its phenomena, demonstrated that they had their own laws and uniformities, and showed how to recognize the symptoms which enable a diagnosis of hysteria to be made. Heredity was to be regarded as the sole cause of hysteria. Charcot’s concern with hypnotic phenomena in hysterical patients led to very great advances in this important field of hitherto neglected and despised facts, for the weight of his name put an end to any doubt about the reality of hypnotic manifestations.

1893

On the psychical mechanism of hysterical phenomena. [cf. its translation into persian: K.Movallali, Sokhan Periodical, 1971, Tehran]

The English translation, “On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena,” is a shorthand report of a lecture delivered and revised by Freud. It is pointed out that all the modern advances made in the understanding and knowledge of hysteria are derived from the work of Charcot. There is an affectively colored experience behind most phenomena of hysteria. If this experience is equated with the major traumatic experience underlying traumatic hysteria the following thesis is derived: there is a complete analogy between traumatic paralysis and common, nontraumatic hysteria. The memories in hysterical patients, which have become pathogenic, occupy an exceptional position as regards the wearing away process; and observation shows that, in the case of all the events which have become determinants of hysterical phenomena, the psychical traumas have not been completely abreacted. There are 2 groups of conditions under which memories become pathogenic. In the first group, the memories to which the hysterical phenomena can be traced back have for their content ideas which involve a trauma so great that the nervous system has not sufficient power to deal with it in any way. In a second group of cases the reason for the absence of a reaction lies not in the content of the psychical trauma but in other circumstances.

1894

The neuro-psychoses of defence (1894).

The problems of the neuroses, which Freud investigated during the years 1893 to 1894, fell into 2 fairly distinct groups, concerned respectively with what were later to become known as the actual neuroses and the psychoneuroses. After making a detailed study of a number of nervous patients suffering from phobias and obsessions, Freud was led to attempt an explanation of these symptoms, thus arriving successfully at the origin of the pathological ideas in new and different cases. The syndrome of hysteria justifies the assumption of a splitting of consciousness, accompanied by the formation of separate psychical groups. The characteristic factor in hysteria is not the splitting of conscious-ness but the capacity for conversion. If someone with a disposition to neurosis lacks the aptitude for conversion, but if, in order to fend off an incompatible idea, he sets about separating it from its affect, then that affect is obliged to remain in the psychical sphere. In all cases that Freud analyzed, it was the subject’s sexual life that had given rise to a distressing affect of precisely the same quality as that attaching to his obsession. In 2 instances considered, defense against the incompatible idea was effected by separating it from its affect; the idea itself remained in consciousness, even though weakened and isolated. In another type of defense the ego rejects the incompatible idea together with its affect and behaves as if the idea had never occurred to the ego at all. But from the moment at which this has been successfully done the subject is in a psychosis, which can only be classified as hallucinatory confusion. The content of a hallucinatory psychosis of this sort consists precisely in the accentuation of the idea which was threatened by the precipitating cause of the onset of illness. The ego has fended off the incompatible idea through escape into psychosis. In summary, a working hypothesis for the neuroses of defense is as follows: In mental functions something is to be distinguished (a quota of affect or sum of excitation) which possess all the characteristics of a quantity which is capable of increase, diminution, displacement and discharge, and which is spread over the memory traces of ideas.

The neuro-psychoses of defence (1894).

Appendix: The emergence of Freud’s fundamental hypotheses.

With the first paper on the neuropsychoses of defense, Freud gives public expression, to many of the most fundamental of the theoretical notions on which all his later work rests. At the time of writing this paper, Freud was deeply involved in the first series of psychological investigations. In his “History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement”, Freud declared that the theory of repression, or defense, to give it its alternative name, is the cornerstone on which the whole structure of psychoanalysis rests. The clinical hypothesis of defense, however, is itself necessarily based on the theory of cathexis. Throughout this period, Freud appeared to regard the cathectic processes as material events. The pleasure principle, no less fundamental than the constancy principle, was equally present, though once more only by implication. Freud regarded the 2 principles as intimately connected and perhaps identical. It is probably correct to suppose that Freud was regarding the quota of affect as a particular manifestation of the sum of excitation. Affect is what is usually involved in the cases of hysteria and obsessional neurosis with which Freud was chiefly concerned in early days. For that reason he tended at that time to describe the displaceable quantity as a quota of affect rather than in more general terms as an excitation; and this habit seems to have persisted even in the metaphysical papers where a more precise differentiation might have contributed to the clarity of his argument.

1895

Obsessions and phobias: Their psychical mechanism and their aetiology (1895).

Obsessions and phobias cannot be included under neurasthenia proper. Since the patients afflicted with these symptoms are no more often neurasthenics than not. Obsessions and phobias are separate neuroses, with a special mechanism and etiology. Traumatic obsessions and phobias are allied to the symptoms of hysteria. Two constituents are found in every obsession: 1) an idea that forces itself upon the patient; and 2) an associated emotional state. In many true obsessions it is plain that the emotional state is the principal thing, since that state persists unchanged while the idea associated with it varies. It is the false connection between the emotional state and the associated idea that accounts for the absurdity so characteristic of obsessions. The great difference between phobias is that in the latter the emotion is always one of anxiety, fear. Among the phobias, 2 groups may be differentiated according to the nature of the object feared: 1) common phobias, an exaggerated fear of things that everyone detests or fears to some extent; and 2) contingent phobias, the fear of special conditions that inspire no fear in the normal man. The mechanism of phobias is entirely different from that of obsessions – nothing is ever found but the emotional state of anxiety which brings up all the ideas adapted to become the subject of a phobia. Phobias then are a part of the anxiety neurosis, which has a sexual origin.

Obsessions and phobias: Their psychical mechanism and their aetiology (1895).

Appendix: Freud’s views on phobias.

Freud’s earliest approach to the problem of phobias was in his first paper on the neuropsychoses of defense. In the earliest of his papers, he attributed the same mechanism to the great majority of phobias and obsessions, while excepting the purely hysterical phobias and the group of typical phobias of which agoraphobia is a model. This later distinction is the crucial one, for it implies a distinction between phobias having a psychical basis and those without. This distinction links with what were later to be known as the psychoneuroses and the actual neuroses. In the paper on obsessions and phobias, the distinction seems to be made not between 2 different groups of phobias but between the obsessions and the phobias, the latter being declared to be a part of the anxiety neurosis. In the paper on anxiety neurosis, the main distinction was not between obsessions and phobias but between phobias belonging to obsessional neurosis and those belonging to anxiety neurosis. There remain undetermined links between phobias, hysteria, obsessions, and anxiety neurosis.

1895

On the grounds for detaching a particular syndrome from neurasthenia under the description “anxiety neurosis” (1895).

Editors’ note, introduction and Part I. The clinical symptomatology of anxiety neurosis.

The paper, “On the Grounds for Detaching a Particular Syndrome from Neurasthenia under the Description Anxiety Neurosis” may be regarded as the first part of a trail that leads through the whole of Freud’s writings. According to Freud, it is difficult to make any statement of general validity about neurasthenia, so long as it is used to cover all the things which Beard has included under it. It was proposed that the anxiety neurosis syndrome be detached from neurasthenia. The symptoms of this syndrome are clinically much more closely related to one another than to those of genuine neurasthenia; and both the etiology and the mechanism of this neurosis are fundamentally different from the etiology and mechanism of genuine neurasthenia. What Freud calls anxiety neurosis may be observed in a completely developed form or in a rudimentary one, in isolation or combined with other neuroses. The clinical picture of anxiety neurosis comprises some of the following symptoms: general irritability; anxious expectation; sudden onslaughts of anxiety; waking up at night in a fright, vertigo, disturbances in digestive activities and attacks of paraesthesias. Several of the symptoms that are mentioned, which accompany or take the place of an anxiety attack, also appear in a chronic form.

1895

On the grounds for detaching a particular syndrome from neurasthenia under the description “anxiety neurosis” (1895).

Part II. Incidence and aetiology of anxiety neurosis.

In some cases of anxiety neurosis no etiology at all is discovered. But where there are grounds for regarding the neurosis as an acquired one, careful inquiry directed to that end reveals that a set of noxae and influences from sexual life are the operative etiological factors. In females, disregarding their innate disposition, anxiety neurosis occurs in the following cases: as virginal anxiety or anxiety in adolescents; as anxiety in the newly married; as anxiety in women whose husbands suffer from ejaculatio praecox or from markedly impaired potency; and whose husbands practice coitus interruptus or reservatus; anxiety neurosis also occurs as anxiety in widows and intentionally abstinent women; and as anxiety in the climacteric during the last major increase of sexual need. The sexual determinants of anxietyneurosis in men include: anxiety of intentionally abstinent men, which is frequently combined with symptoms of defense; anxiety in men in a state of unconsummated excitation, or in those who content themselves with touching or looking at women; anxiety in men who practice coitus interruptus; and anxiety in senescent men. There are 2 other cases which apply to both sexes. 1) People who, as a result of practicing masturbation, have been neurasthenics, fall victim to anxiety neurosis as soon as they give up their form of sexual satisfaction. 2) Anxiety neurosis arises as a result of the factor of overwork or exhausting exertion.

1895

On the grounds for detaching a particular syndrome from neurasthenia under the description “anxiety neurosis” (1895).

Part III. First steps towards a theory of anxiety neurosis.

According to Freud, the mechanism of anxiety neurosis is to be looked for in a deflection of somatic sexual excitation from the psychical sphere, and in a consequent abnormal employment of that excitation. This concept of the mechanism of anxiety neurosis can be made clearer if the following view of the sexual process, which applies to men, is accepted. In the sexually mature male organism, somatic sexual excitation is produced and periodically becomes a stimulus to the psyche. The group of sexual ideas which is present in the psyche becomes supplied with energy and there comes into being the physical state of libidinal tension which brings with it an urge to remove that tension. A psychical unloading of this kind is possible only by means of what is called specific or adequate action. Anything other than the adequate action would be fruitless, for once the somatic sexual excitation has reached threshold value, it is turned continuously into psychical excitation and something must positively take place which will free the nerve endings from the pressure on them. Neurasthenia develops whenever the adequate unloading is replaced by a less adequate one. This view depicts the symptoms of anxiety neurosis as being in a sense surrogates of the omitted specific action following on sexual excitation. In the neurosis, the nervous system is reacting against a source of excitation which is internal, whereas in the corresponding affect it is reacting against an analogous source of excitation which is external.

On the grounds for detaching a particular syndrome from neurasthenia under the description “anxiety neurosis” (1895).

Part IV. Relation to other neuroses.

The purest cases of anxiety neurosis, usually the most marked, are found in sexually potent youthful individuals, with an undivided etiology, and an illness that is not too long standing. More often, however, symptoms of anxiety occur at the same time as, and in combination with symptoms of neurasthenia, hysteria, obsessions, or melancholia. Wherever a mixed neurosis is present, it will be possible to discover an intermixture of several specific etiologies. The etiological conditions must be distinguished for the onset of the neuroses from their specific etiological factors. The former are still ambiguous, and each of them can produce different neuroses. Only the etiological factors which can be picked out in them, such as inadequate disburdening, psychical insufficiency or defense accompanied by substitution, have an unambiguous and specific relation to the etiology of the individual major neuroses. Anxiety neurosis presents the most interesting agreement with, and differences from, the other major neuroses, in particular neurasthenia and hysteria. It shares with neurasthenia one main characteristic, namely, that the source of excitation lies in the somatic field instead of the psychical one as is the case in hysteria and obsessional neurosis. The symptomatology of hysteria and anxiety neurosis shows many points in common. The appearance of the following symptoms either in a chronic form or in attacks, the paraesthesias, the hyperaesthesias and pressure points are found in both hysterias and anxiety attacks.

On the grounds for detaching a particular syndrome from neurasthenia under the description “anxiety neurosis” (1895).

Appendix: The term “Angst” and its English translation.

There are at least 3 instances in which Freud discusses the various shades of meaning expressed by the German word Angst and the cognate Furcht and Schreck. Though he stresses the anticipatory element and absence of an object in Angst, the distinctions he draws are not entirely convincing, and his actual usage is far from invariably obeying them. Angst may be translated to many similarly common English words: fear, fright, alarm, etc. Angst often appears as a psychiatric term: The word universally adopted for the purpose has been anxiety. The English translator is driven to compromise: He must use anxiety in technical or semitechnical connections, and must elsewhere choose whatever everyday English word seems most appropriate.

1895

A reply to criticisms of my paper on anxiety neurosis (1895).

A reply to Lowenfeld’s criticisms of Freud’s paper (January 1895) on anxiety neurosis is presented. It is Freud’s view that the anxiety appearing in anxiety neurosis does not admit of a psychical derivation and he maintains that fright must result in hysteria or a traumatic neurosis, but not in an anxiety neurosis. Lowenfeld insists that in a number of cases ‘states of anxiety’ appear immediately or shortly after a psychical shock. Freud states that in the etiology of the neuroses, sexual factors play a predominant part. Lowenfeld relates experiences where he has seen anxiety states appear and disappear when a change in the subject’s sexual life had not taken place but where other factors were in play. The following concepts are postulated in order to understand the complicated etiological situation which prevails in the pathology of the neuroses: precondition, specific cause, concurrent causes, and precipitating or releasing cause. Whether a neurotic illness occurs at all depends upon a quantitative factor, upon the total load on the nervous system as compared with the latter’s capacity for resistance. What dimensions the neurosis attains depends in the first instance on the amount of the hereditary taint. What form the neurosis assumes is solely determined by the specific etiological factor arising from sexual life.

1896

Heredity and the aetiology of the neuroses (1896).

The paper, “Heredity and the Etiology of the Neuroses” is a summary of Freud’s contemporary view on the etiology of all 4 of what he then regarded as the main types of neurosis: the 2 psychoneuroses, hysteria and obsessional neurosis; and the 2 actual neuroses, neurasthenia and anxiety neurosis. Opinion of the etiological role of heredity in nervous illness ought to be based on an impartial statistical examination. Certain nervous disorders can develop in people who are perfectly healthy and whose family is above reproach. In nervous pathology, there is similar heredity and also dissimilar heredity. Without the existence of a special etiological factor, heredity could do nothing. The etiological influences, differing among themselves in their importance and in the manner in which they are related to the effect they produce, can be grouped into 3 classes: preconditions, concurrent causes, and specific causes. In the pathogenesis of the major neuroses, heredity fulfills the role of a precondition. Some of the concurrent causes of neuroses are: emotional disturbance, physical exhaustion, acute illness, intoxications, traumatic accidents, etc. The neuroses have as their common source the subject’s sexual life, whether they lie in a disorder of his contemporary sexual life or in important events in his past life.

1896

Further remarks on the neuro-psychoses of defence (1896).

Part I. The “specific” aetiology of hysteria.

“Further Remarks on the Neuropsychoses of Defense” takes up the discussion at a point that Freud reached in his first paper, (1894). The ultimate case of hysteria is always the seduction of a child by an adult. The actual traumatic event always occurs before the age of puberty, though the outbreak of the neurosis occurs after puberty. This whole position is later abandoned by Freud, and its abandonment signalizes a turning point in his views. In a short paper published in 1894, Freud grouped together hysteria, obsessions, and certain cases of acute hallucinatory confusion under the name of neuropsychoses of defense because those affections turned out to have one aspect in common. This was that their symptoms arose through the psychical mechanism of defense, that is, in an attempt to repress an incompatible idea which had come into distressing opposition to the patient’s ego. The symptoms of hysteria can only be understood if they are traced back to experiences which have a traumatic effect. These psychical traumas refer to the patient’s sexual life. These sexual traumas must have occurred in early childhood and their content must consist of an actual irritation of the genitals. All the experiences and excitations which, in the period of life after puberty, prepare the way for, or precipitate, the outbreak of hysteria, demonstrably have their effect only because they arouse the memory trace of these traumas in childhood, which do not thereupon become conscious but lead to a release of affect and to repression. Obsessions also presuppose a sexual experience in childhood.

1896

Further remarks on the neuro-psychosis of defence (1896).

Part II. The nature and mechanism of obsessional neurosis.

Sexual experiences of early childhood have the same significance in the etiology of obsessional neurosis as they have in that of hysteria. In all the cases of obsessional neurosis, Freud found a substratum of hysterical symptoms which could be traced back to a scene of sexual passivity that preceded the pleasurable action. Obsessional ideas are transformed self-reproaches which have reemerged from repression and which relate to some sexual act that was performed with pleasure in childhood. In the first period, childhood immorality, events occur which contain the germ of the later neurosis. This period is brought to a close by the advent of sexual maturation. Self-reproach now becomes attached to the memory of these pleasurable actions. The second period, illness, is characterized by the return of the repressed memories. There are 2 forms of obsessional neurosis, according to whether what forces an entrance into consciousness is solely the mnemic content of the act involving self-reproach, or whether the self-reproachful affect connected with the act does so as well. The first form includes the typical obsessional ideas, in which the content engages the patient’s attention and, he merely feels an indefinite unpleasure, whereas the only affect which would be suitable to the obsessional idea would be one of self-reproach. A second form of obsessional neurosis comes about if what has forced its way to representation in conscious psychical life is not the repressed mnemic content but the repressed self-reproach.

1896

Further remarks on the neuro-psychosis of defense (1896).

Part III. Analysis of a case of chronic paranoia.

Freud postulates that paranoia, like hysteria and obsessions, proceeds from the repression of distressing memories and that its symptoms are determined in their form by the content of what has been repressed. The analysis of a case of chronic paranoia is presented. Frau P., 32 years of age, has been married for 3 years and is the mother of a 2-year-old child. Six months after the birth of her child, she became uncommunicative and distrustful, showed aversion to meeting her husband’s brothers and sisters and complained that the neighbors in the small town in which she lived were rude and inconsiderate to her. The patient’s depression began at the time of a quarrel between her husband and her brother. Her hallucinations were part of the content of repressed childhood experiences, symptoms of the return of the repressed while the voices originated in the repression of thoughts which were self-reproaches about experiences that were analogous to her childhood trauma. The voices were symptoms of the return of the repressed. Part of the symptoms arose from primary defense, namely, all the delusional ideas which were characterized by distrust and suspicion and which were concerned with ideas of being persecuted by others. Other symptoms are described as symptoms of the return of the repressed. The delusional ideas which have arrived in consciousness by means of a compromise make demands on the thought activity of the ego until they can be accepted without contradiction.

1896

The aetiology of hysteria (1896).

“The Etiology of Hysteria” may be regarded as an amplified repetition of the first section of its predecessor, the second paper on the neuropsychoses of defense. No hysterical symptom can arise from a real experience alone, but in every case, the memory of earlier experiences plays a part in causing the symptoms. Whatever case and symptom are taken as out point of departure leads to the field of sexual experience. After the chains of memories have converged, we come to the field of sexuality and to a small number of experiences which occur for the most part at the same period of life, namely, at puberty. If we press on with the analysis into early childhood, we bring the patient to reproduce experiences which are regarded as the etiology of his neurosis. Freud put forward the thesis that for every case of hysteria there are one or more occurrences of premature sexual experience, occurrences which belong to the earliest years of childhood but which can be reproduced through the work of psychoanalysis in spite of the intervening decades. Sexual experiences in childhood consisting in stimulation of the genitals must be recognized as being the traumas which lead to a hysterical reaction to events at puberty and to the development of hysterical symptoms. Sensations and paraesthesias are the phenomena which correspond to the sensory content of the infantile scenes, reproduced in a hallucinatory fashion and often painfully intensified.

1898

Sexuality in the aetiology of the neuroses (1896).

In every case of neurosis there is a sexual etiology; but in neurasthenia it is an etiology of a present day kind, whereas in the psychoneuroses the factors are of an infantile nature. The sexual causes are the ones which most readily offer the physician a foothold for his therapeutic influence. When heredity is present, it enables a strong pathological effect to come about where otherwise only a very slight one would have resulted. Neurasthenia is one of those affections which anyone might easily acquire without having any hereditary taint. It is only the sexual etiology which makes it possible for us to understand all the details of the clinical history of neurasthenics, the mysterious improvements in the middle of the course of the illness and the equally incomprehensible deteriorations, both of which are usually related by doctors and patients to whatever treatment has been adopted. Since the manifestations of the psychoneuroses arise from the deferred action of unconscious psychical traces, they are accessible to psychotherapy. The main difficulties which stand in the way of the psychoanalytic method of cure are due to the lack of understanding among doctors and laymen of the nature of the psychoneuroses.

1898

The psychical mechanism of forgetfulness (1898).

The phenomenon of forgetfulness, which has been universally experienced, usually affects proper names. Two accompanying features of forgetfulness are an energetic deliberate concentration of attention which proves powerless, to find the lost name and in place of the name we are looking for, another name promptly appears, which we recognize as incorrect and reject, but which persists in coming back. The best procedure of getting hold of the missing name is not to think of it and after a while, the missing name shoots into one’s mind. While Freud was vacationing, he went to Herzegovina. Conversation centered around the condition of the 2 countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina), and the character of their inhabitants. The discussion turned to Italy and of pictures. Freud recommended that his companions visit Orvieto some time, in order to see the frescoes there of the End of the World and the Last Judgement. Freud was unable to think of the artist’s name. He could only think of Botticelli and Boltraffio. He had to put up with this lapse of memory for several days until he met someone who told him that the artist’s name was Luca Signorelli. Freud interpreted the forgetting as follows: icelli contains the same final syllables as Signorelli; the name Bosnia showed itself by directing the

1899

Screen memories (1899).

The age to which the content of the earliest memories of childhood is usually referred back is the period between the ages of 2 and 4. The most frequent content of the first memories of childhood are occasions of fear, shame, physical pain, etc., and important events such as illnesses, deaths, fires; births of brothers and sisters, etc. A case is presented of a man of university education, aged 38, who moved at the age of 3. His memories of his first place of residence fall into 3 groups. The first group consists of scenes of which his parents have repeatedly since described to him. The second group comprises scenes which have not been described and some of which could not have been described to him. The pictures and scenes of the first 2 groups are probably displaced memories from which the essential element has for the most part been omitted. In the third group, there is material, which cannot be understood. Two sets of phantasies were projected onto one another and a childhood memory was made of them. A screen memory is a recollection whose value lies in that it represents in the memory impressions and thoughts of a later date whose content is connected with its own by symbolic or similar links. The concept of screen memory owes its value as a memory not to its own content but to the relation existing between that content and some other, that has been suppressed. Different classes of screen memories can be distinguished according to the nature of that relation. A screen memory may be described as retrogressive. Whenever in a memory the subject himself appears as an object among other objects, the contrast between the acting and the recollecting ego may be taken as evidence that the original impression has been worked over.

1901

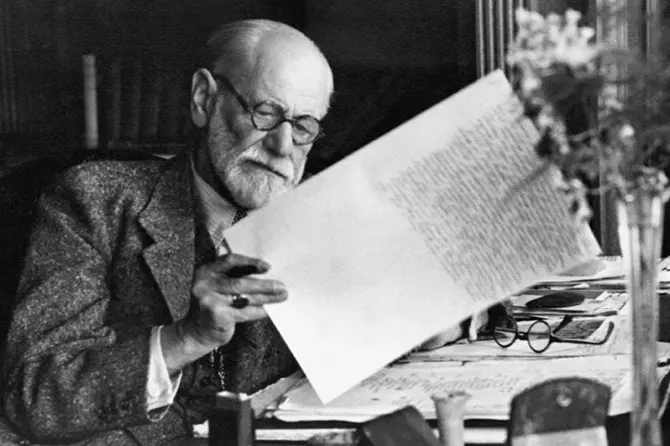

Autobiographical note (1901).

Freud’s autobiographical note, written in the autumn of 1899 is presented. He regarded himself as a pupil of Brucke and of Charcot. His appointment as Privatdozent was in 1885 and he worked as physician and Dozent at Vienna University after 1886. Freud produced earlier writings on histology and cerebral anatomy, and subsequently, clinical works on neuropathology; he translated writings by Charcot and Bernheim. Since 1895, Freud turned to the study of the psychoneuroses and especially hysteria, and in a series of shorter works he stressed the etiological significance of sexual life for the neuroses. He has also developed a new psychotherapy of hysteria, on which very little has been published. TOP

1900 to1920

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter I: The scientific literature dealing with the problems of dreams.

(A) The relation of dreams to waking life.

The scientific literature dealing with the problems of dreams is discussed. The prescientific view of dreams adopted by the peoples of antiquity was in complete harmony with their view of the universe in general, which led them to project into the external world as though they were realities, things which in fact enjoyed reality only within their own minds. The unsophisticated waking judgment of someone who has just awakened from sleep assumes that his dreams, even if they did not themselves come from another world, had carried him off into another world. Two views of the relation of dreams to waking life are discussed: 1) that the mind is cut off in dreams, almost without memory, from the ordinary content and affairs of waking life or 2) that dreams carry on waking life and attach themselves to the ideas previously residing in consciousness. Due to the contradiction between these 2 views, a discussion of the subject is presented by Hildebrandt who believes that it is impossible to describe the characteristics of dreams at all except by means of a series of (3) contrasts which seem to sharpen into contradictions. It is concluded that the dream experience appears as something alien inserted between 2 sections of life which are perfectly continuous and consistent with each other.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter I: The scientific literature dealing with the problems of dreams.

(B) The material of dreams-Memory in dreams.

All the material making up the content of a dream is in some way derived from experience. Dreams have at their command memories which are inaccessible in waking life. It is a very common event for a dream to give evidence of knowledge and memories which the waking subject is unaware of possessing. One of the sources from which dreams derive materials for reproduction, material which is in part neither remembered nor used in the activities of waking thought, is childhood experience. A number of writers assert that elements are to be found in most dreams, which are derived from the last very few days before they were dreamt. The most striking and least comprehensible characteristic of memory in dreams is shown in the choice of material reproduced: what is found worth remembering is not, as in waking life, only what is most important, but what is most indifferent and insignificant. This preference for indifferent, and consequently unnoticed, elements in waking experience is bound to lead people to overlook the dependence of dreams upon waking life and to make it difficult in any particular instance to prove that dependence. The way memory behaves in dreams is of the greatest importance for any theory of memory in general.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter I: The scientific literature dealing with the problems of dreams.

(C) The stimuli and sources of dreams.

There are 4 kinds of sources of dreams: external (objective) sensory excitations; internal (subjective) sensory excitations; internal (organic) somatic stimuli; and purely psychical sources of stimulation. There are a great number of sensory stimuli that reach us during sleep, ranging from unavoidable ones which the state of sleep itself necessarily involves or must tolerate, to the accidental, rousing stimuli which may or do put an end to sleep. As sources of dream images, subjective sensory excitations have the advantage of not being dependent, like objective ones, upon external chance. The body, when in a diseased state, becomes a source of stimuli for dreams. In most dreams, somatic stimuli and the psychical instigators work in cooperation.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter I: The scientific literature dealing with the problems of dreams.

(D) Why dreams are forgotten after waking.

It is a proverbial fact that dreams melt away in the morning. All the causes that lead to forgetting in waking life are operative for dreams as well. Many dream images are forgotten because they are too weak, while stronger images adjacent to them are remembered. It is in general as difficult and unusual to retain what is nonsensical as it is to retain what is confused and disordered. Dreams, in most cases, are lacking in intelligibility and orderliness. The compositions which constitute dreams are barren of the qualities (strength intensity, nonunique experience, orderly groupings) which would make it possible to remember them, and they are forgotten because as a rule they fall to pieces a moment after awakening, and because most people take very little interest in their dreams.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter I: The scientific literature dealing with the problems of dreams.

(E) The distinguishing psychological characteristics of dreams.

It is assumed that dreams are products of our own mental activity. One of the principal peculiarities of dream life makes its appearance during the very process of falling asleep and may be described as a phenomenon heralding sleep. Dreams think predominantly in visual images, but make use of auditory images as well. In dreams, the subjective activity of our minds appears in an objective form, for our perceptive faculties regard the products of our imagination as though they were sense impressions. Sleep signifies an end of the authority of the self, hence, falling asleep brings a certain degree of passivity along with it. The literature that involves the psychological characteristics of dreams shows a very wide range of variation in the value which it assigns to dreams as psychical products. This range extends from the deepest disparagement through hints at a yet undisclosed worth, to an overvaluation which ranks dreams far higher than any of the functions of waking life.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter I: The scientific literature dealing with the problems of dreams.

(F) The moral sense in dreams.

The moral sense in dreams is discussed. Some assert that the dictates of morality have no place in dreams, while others maintain that the moral character of man persists in his dream life. Those who maintain that the moral personality of man ceases to operate in dreams should, in strict logic, lose all interest in immoral dreams. Those who believe that morality extends to dreams are careful to avoid assuming complete responsibility for their dreams. The emergence of impulses which are foreign to our moral consciousness is merely analogous to the fact that dreams have access to ideational material which is absent in our waking state or plays but a small part in it. Affects in dreams cannot be judged in the same way as the remainder of their content; and we are faced by the problem of what part of the psychical processes occurring in dreams is to be regarded as real (has a claim to be classed among the psychical processes of waking life).

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter I: The scientific literature in dealing with the problems of dreams.

(G) Theories of dreaming and its function.

Theories of dreaming and its function are discussed. Some theories (i.e. Delboeuf) states that the whole of psychical activity continues in dream. The mind does not sleep and its apparatus remains intact; but, since it falls under the conditions of the state of sleep, its normal functioning necessarily produces different results during sleep. There are other theories which presuppose that dreams imply a lowering of psychical activity, a loosening of connections, and an impoverishment of the material accessible. These theories must imply the attribution to sleep of characteristics quite different from those suggested by Delboeuf. A third group of theories ascribe to the dreaming mind a capacity and inclination for carrying out special psychical activities of which it is largely or totally incapable in waking life. The putting of these faculties into force usually provides dreaming with a utilitarian function. The explanation of dreaming by Schemer as a special activity of the mind, capable of free expansion only during the state of sleep is presented. He states that the material with which dream imagination accomplishes its artistic work is principally provided by the organic somatic stimuli which are obscure during the daytime.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter I: The scientific literature dealing with the problems of dreams.

(H) The relations between dreams and mental diseases.

When we speak of the relation of dreams to mental disorders we may have 3 things in mind: 1) etiological and clinical connections, as when a dream represents a psychotic state, or introduces it, or is left over from it; 2) modifications to which dream life is subject in cases of mental disease; and 3) intrinsic connections between dreams and psychoses, analogies pointing to their being essentially akin. In addition to the psychology of dreams physicians will some day turn their attention to psychopathology of dreams. In cases of recovery from mental diseases it can often be observed that while functioning is normal during the day, dream life is still under the influence of the psychosis. The indisputable analogy between dreams and insanity is one of the most powerful factors of the medical theory of dream life which regards dreaming as a useless and disturbing process and as the expression of a reduced activity of the mind.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter II: The method of interpreting dreams: An analysis of a specimen dream.

The method of interpreting dreams is presented. The aim that Freud sets is to show that dreams are capable of being interpreted. The lay world has hitherto made use of 2 essentially different methods: 1) It considers the content of the dream as a whole and seeks to replace it by another content which is intelligible and in certain respects analogous to the original one, this is (symbolic dream interpreting). 2) The decoding method, which treats dreams as a kind of cryptography in which each sign can be translated into another sign having a known meaning, in accordance with a fixed key. Neither of the 2 popular procedures for interpreting dreams can be employed for a scientific treatment of the subject. The object of the attention is not the dream as a whole but the separate portions of its content.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter II: The method of interpreting dreams: An analysis of a specimen dream (preamble and dream).

An analysis of one of Freud’s dreams, the dream of July twenty 4hird to the twenty-fourth, 1895, is presented. During the summer of 1895, Freud had been giving psychoanalytic treatment to a woman who was on very friendly terms with him and his family. This woman was involved in the dream as a central figure (Irma). The dream was analyzed, one line or thought at a time. The dream fulfilled certain wishes which were initiated by the events of the previous evening. The conclusion of the dream was that Freud was not responsible for the persistence of Irma’s pains, but that Otto (a junior colleague) was. Otto had annoyed Freud by his remarks about Irma’s incomplete cure, and the dream gave Freud his revenge by throwing the reproach back. Certain other themes played a part in the dream, which were not so obviously connected with his exculpation from Irma’s illness: his daughter’s illness and that of his patient who bore the same name, the injurious effect of cocaine, the disorder of his patient who was traveling in Egypt, his concern about his wife’s health and about that of his brother and of Dr. M., his own physical ailments, and his anxiety about his absent friend who suffered from suppurative rhinitis. Freud concluded that when the work of interpretation is completed, it is perceived that a dream is the fulfillment of a wish.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter III: A dream is the fulfillment of a wish.

It is easy to prove that dreams often reveal themselves as fulfillments of wishes. In a dream of convenience, dreaming has taken the place of action, as it often does elsewhere in life. Dreams which can only be understood as fulfillments of wishes and which bear their meaning upon their faces without disguise are found under the most frequent and various conditions. They are mostly short and simple dreams, which afford a pleasant contrast to the confused and exuberant compositions that have in the main attracted the attention of the authorities. The dreams of young children are frequently pure wish fulfillments and are subsequently quite uninteresting compared with the dreams of adults. A number of cases of dreams of children are presented and interpreted.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter IV: Distortion in dreams.

The fact that the phenomena of censorship and of dream distortion correspond to their smallest details justifies assumption that they are similarly determined, therefore, it is supposed that dreams are given their shape in individual human beings by the operation of 2 psychical forces; and that one of these forces constructs the wish which is expressed by the dream, while the other exercises a censorship upon this dream wish and, by the use of that censorship, forcibly brings about a distortion in the expression of the wish. The very frequent dreams, which appear to stand in contradiction to Freud’s theory because their subject matter is the frustration of a wish or the occurrence of something clearly unwished for, may be brought together under the heading of counter wish dreams. If these dreams are considered as a whole, it seems possible to trace them back to 2 principles. One of the 2 motive forces is the wish that Freud may be wrong, the second motive involves the masochistic component in the sexual constitution of many people. Those who find their pleasure, not in having physical pain inflicted on them, but in humiliation and mental torture, may be described as mental masochists. People of this kind can have counter wish dreams and unpleasurable dreams, which are none the less wish fulfillments since they satisfy their masochistic inclinations. Anxiety dreams (a special subspecies of dreams with a distressing content) do not present a new aspect of the dream problem but present the question of neurotic anxiety. The anxiety that is felt in a dream is only apparently explained by the dream’s content. In cases of both phobias and anxiety dreams the anxiety is only superficially attached to the idea that accompanies it; it originates from another source. Since neurotic anxiety is derived from sexual life and corresponds to libido which has been diverted from its purpose and has found no employment, it can be inferred that anxiety dreams are dreams with a sexual content, the libido belonging to that which has been transformed into anxiety.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter V: The material and sources of dreams.

(A) Recent and indifferent material in dreams.

Recent and indifferent material and sources of dreams are discussed. Dreams show a clear preference for the impressions of the immediately preceding days and make their selection upon different principles from our waking memory, since they do not recall what is essential and important but what is subsidiary and unnoticed. Dreams have at their disposal the earliest impressions of childhood and details from that period of life which is trivial and which in the waking state are believed to have been long forgotten. In each of Freud’s dreams, it is possible to find a point of contact with the experiences of the previous day. The instigating agent of every dream is to be found among the experiences which one has not yet slept on. Dreams can select their material from any part of the dreamer’s life, provided that there is a train of thought linking the experience of the dream day with the earlier ones. The analysis of a dream will regularly reveal its true, psychically significant source in waking life, though the emphasis has been displaced from the recollection of that source on to that of an indifferent one. The source of a dream may be either: 1) a recent and psychically significant experience, 2) several recent and significant experiences combined into 1 unit by the dream, 3) 1 or more recent and significant experiences represented in the dream content by a mention of a contemporary but indifferent experience or 4) an internal significant experience which is invariably represented in the dream by mention of a contemporary but indifferent impression. Considering these 4 cases, a psychical element which is significant but not recent can be replaced by an element which is recent but indifferent provided 1) the dream content is connected with a recent experience, and 2) the dream instigator remains a psychically significant process. Freud concludes that there are no indifferent dream instigators, therefore, no innocent dreams.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter V: The material and sources of dreams.

(B) Infantile material as a source of dreams.

Infantile material is discussed as a source of dreams. Experiences from childhood play a part in dreams whose content would never have led one to suppose it. In the case of another group of dreams, analysis shows that the actual wish which instigated the dream, and the fulfillment of which is represented by the dream, is derived from childhood, so that we find the child and the child’s impulses still living on in the dream. The deeper one carries the analysis of a dream, the more often one comes upon the track of experiences in childhood which have played a part among the sources of that dream’s latent content. Trains of thought reaching back to earliest childhood lead off even from dreams which seem at first sight to have been completely interpreted, since their sources and instigating wish have been discovered without difficulty. Dreams frequently seem to have more than one meaning. Not ouly may they include several wish fulfillments, one alongside the other, but a succession of meanings or wish fulfillments may be superimposed on one another, the bottom one being the fulfillment of a wish dating from earliest childhood.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter V: The material and sources of dreams.

(C) The somatic sources of dreams.

The somatic sources of dreams are discussed. There are 3 different kinds of somatic sources of stimulation: objective sensory stimuli arising from external objects, internal states of excitation of the sense organs having only a subjective basis, and somatic stimuli derived from the interior of the body. The significance of objective excitations of the sense organs is established from numerous observations and has been experimentally confirmed. The part played by subjective sensory excitations is demonstrated by the recurrence in dreams of hypnagogic sensory images. Though it is impossible to prove that the images and ideas occurring in dreams can be traced to internal somatic stimuli, this origin finds support in the universally recognized influence exercised upon dreams by states of excitation in digestive, urinary, and sexual organs. When external nervous stimuli and internal somatic stimuli are intense enough to force psychical attention to themselves, they then serve as a fixed point for the formation of a dream, a nucleus in its material; a wish fulfillment is then desired that shall correspond to this nucleus. Somatic sources of stimulation during sleep, unless they are of unusual intensity, play a similar part in the formation of dreams to that played by recent but indifferent impressions remaining from the previous day.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter V: The material and sources of dreams.

(D) Typical dreams: (a) Embarassing dreams of being naked.

There are a certain number of typical dreams which almost everyone has dreamt and which we assume must have the same meaning for everyone. Dreams of being naked or insufficiently dressed in the presence of strangers sometimes occur with the additional feature of their being a complete absence of any such feeling of shame on the dreamer’s part. Freud is concerned only with those dreams of being naked in which one does feel shame and embarassment and tries to escape or hide, and is then overcome by a strange inhibition which prevents one from moving and makes one feel incapable of altering the distressing situation. The nature of the undress involved is customarily far from clear. The people in whose presence one feels ashamed are almost always strangers, with their features left indeterminate. The core of a dream of exhibiting lies in the figure of the dreamer himself (not as he was as a child but as he appears at the present time) and his inadequate clothing (which emerges indistinctly, whether owing to superimposed layers of innumerable later memories of being in undress or as a result of the censorship). Repression plays a part in dreams of exhibiting; for the distress felt in such dreams is a reaction against the content of the scene of exhibiting having found expression in spite of the ban upon it.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter V: The material and sources of dreams.

(D) Typical dreams: (b) Dreams of the death of persons of whom the dreamer is fond.

There is a group of dreams which contains the death of some loved relative; for instance, of a parent, of a brother or sister, or of a child. Two classes of such dreams are distinguished: those in which the dreamer is unaffected by grief, so that on awakening he is astonished at his lack of feeling, and those in which the dreamer feels deeply pained by the death and may even weep bitterly in his sleep. Analyses of the dreams of class 1 show that they have some meaning other than the apparent one, and that they are intended to conceal some other wish. The meaning of the second class of dreams, as their content indicates, is a wish that the person in question may die. A child’s death wishes against his brothers and sisters are explained by the childish egoism which makes him regard them as his rivals. Dreams of the death of parents apply with preponderant frequency to the parent who is of the same sex as the dreamer. It is as though a sexual preference were making itself felt at an early age: as though boys regarded their fathers and girls their mothers as their rivals in love, whose elimination could not fail to be to their advantage.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter V: The material and sources of dreams.

(D) Typical dreams: (c) Other typical dreams.

Since Freud has no experience of his own regarding other typical dreams in which the dreamer finds himself flying through the air to the accompaniment of agreeable feelings or falling with feelings of anxiety, he uses information provided by psychoanalysis to conclude that these dreams reproduce impressions of childhood and they relate to games involving movement, which are extraordinarily attractive to children. What provokes dreams of flying and falling is not the state of the tactile feelings during sleep or sensations of the movement of lungs: These sensations are themselves reproduced as part of the memory to which the dream goes back: rather, they are part of the content of the dream and not its source. All the tactile and motor sensations which occur in these typical dreams are called up immediately when there is any psychical reason for making use of them and they can be disregarded when no such need arises. The relation of these dreams to infantile experiences has been established due to indications from the analyses of psychoneurotics.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter V: The material and sources of dreams.

(D) Typical dreams: (d) Examination dreams.

Everyone who has passed the matriculation examination at the end of his school studies complains of the obstinacy with which he is pursued by anxiety dreams of having failed, or of being obliged to take the examination again, etc. In the case of those who have obtained a University degree this typical dream is replaced by another one which represents them as having failed in the University finals; and it is in vain that they object, even while still asleep, that for a year they have been practicing medicine or working as University lecturers or heads of offices. The examination anxiety of neurotics owes its intensification to childhood fears. Anxious examination dreams search for some occasion in the past in which great anxiety has turned out to be unjustified and has been contradicted by the event. This situation would be a striking instance of the content of a dream being misunderstood by the waking agency (the dreamer).

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work:

(A) The work of condensation.

Every attempt that has hitherto been made to solve the problem of dreams has dealt directly with their manifest content as it is presented in memory. The dream thoughts and the dream content are presented like 2 versions of the same subject matter in 2 different languages. The dream content seems like a transcript of dream thoughts into another mode of expression, whose characters are syntactic laws are discovered by comparing the original and the translation. The dream thoughts are immediately comprehensible, as soon as we have learned them. The dream content is expressed as it were in a pictographic script, the characters of which have to be transposed individually into the language of the dream thoughts. The first thing that becomes clear to anyone who compares the dream content with the dream thoughts is that a work of condensation on a large scale has been carried out. Dreams are brief, meager, and laconic in comparison with the range and wealth of the dream thoughts. The work of condensation in dreams is seen at its clearest when it handles words and names. The verbal malformations in dreams greatly resemble those which are familiar in paranoia but which are also present in hysteria and obsessions. When spoken sentences occur in dreams and are expressly distinguished as such from thoughts, it is an invariable rule that the words spoken in the dream are derived from spoken words remembered in the dream material.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work. (B) The work of displacement.

The dream is differently centered from the dream thoughts; its content has different elements as its central point. It seems plausible to suppose that in dream work a psychical force is operating which strips the elements which have a high psychical value of their intensity and, by means of overdetermination, creates from elements of low psychical value new values, which afterwards find their way into the dream content. If that is so, a transference and displacement of psychical intensities occurs in the process of dream formation, and it is as a result of these that the difference between the test of the dream content and that of the dream thoughts come about. We may assume that dream displacement comes about through the influence of the censorship of endopsychic defense. Those elements of the dream thoughts which make their way into the dream must escape the censorship imposed by resistance.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work. (C) The means of representation in dreams.

The means of representation in dreams are discussed. In the process of transforming the latent thoughts into the manifest content of a dream, 2 factors are at work: dream condensation and dream displacement. The logical relation between the dream thoughts are not given any separate representation in dreams. If a contradiction occurs in a dream, it is either a contradiction of the dream itself or a contradiction derived from the subject matter of one of the dream thoughts. Dreams take into account the connection which undeniably exists between all the portions of the dream thoughts by combining the whole material into a single situation or event. Similarity, consonance, and the possession of common attributes are all represented in dreams by unification which may either by already present in the material of the dream thoughts or may be freshly constructed. Identification or the construction of composite figures serves various purposes in dreams: firstly to represent an element common to 2 persons, secondly to represent a displaced common element, and thirdly, to express a merely wishful common element. The content of all dreams that occur during the same night forms part of the same whole; the fact of their being divided into several sections, as well as the groupings and number of those sections has a meaning and may be regarded as a piece of information arising from the latent dream thoughts.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work.

(D) Considerations of representability.

The material of the dream thoughts, stripped to a large extent of its interrelations, is submitted to a process of compression, while at the same time displacements of intensity between its elements necessarily bring about a psychical transvaluation of the material. There are 2 sorts of displacements. One consists in the replacing of a particular idea by another in some way closely associated with it, and they are used to facilitate condensation in so far as, instead of 2 elements, a single common element intermediate between them finds its way into the dream. Another displacement exists and reveals itself in a change in verbal expression of the thoughts concerned. The direction taken by the displacement usually results in the exchange of a colorless and abstract expression in dream thought for a pictorial and concrete one. Of the various subsidiary thoughts attached to the essential dream thoughts, those which admit of visual representations will be preferred. The dream work does not shrink from the effort of recasting unadaptable thoughts into a new verbal form, provided that that process facilitates representation and so relieves the psychological pressure caused by constricted thinking.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work.

(E) Representation by symbols in dreams-Some further typical dreams.

Since symbolism is used for representing sexual material in dreams, the question arises whether many of these symbols do not occur with a permanently fixed meaning. This symbolism is not peculiar to dreams, but is characteristic of unconscious ideation, in particular among the people (laymen). It is to be found in folklore, in popular myths, legends, linguistic idioms, proverbial wisdom and current jokes, to a more complete extent than in dreams. The following ideas or objects show dream representation by symbols: a hat as a symbol of a man or of male genitals; a little hat as the genital organ; being run over as a symbol of sexual intercourse; the genitals represented by buildings, stairs, and shafts; the male organ represented by persons and the female organ by a landscape. The more one is concerned with the solution of dreams, the more one is driven to recognize that the majority of the dreams of adults deal with sexual material and give expression to erotic wishes. Many dreams, if they are carefully interpreted, are bisexual, since they unquestionably admit of an over interpretation in which the dreamer’s homosexual impulses are realized, impulses which are contrary to his normal sexual activities. A large number of dreams, often accompanied by anxiety and having as their content such subjects as passing through narrow spaces or being in water, are based upon phantasies of intrauterine life, of existence in the womb, and of the act of birth.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work.

(F) Some examples. Calculations and speeches in dreams.

A few instances of peculiar or unusual modes of representation in dreams are presented. For the purpose of representation in dreams, the spelling of words is far less important than their sound. The dream work makes use, for the purpose of giving a visual representation of the dream thoughts, of any methods within its reach, whether waking criticism regards them as legitimate or illegitimate. The dream work can often succeed in representing very refractory material, such as proper names, by a farfetched use of out-of4he-way associations. The dream work does not in fact carry out any calculations at all, whether correctly or incorrectly; it merely throws into the form of a calculation numbers which are present in the dream thoughts and can serve as allusions to matter that cannot be represented in any other way. The dream work treats numbers as a medium for the expression of its purpose in precisely the same way as it treats any other idea, including proper names and speeches that occur recognizably as verbal presentations. The dream work cannot actually create speeches. However much speeches and conversations, whether reasonable or unreasonable in themselves, may figure in dreams, analysis invariably proves that all that the dream has done is to extract from the dream thoughts fragments of speeches which have really been made or heard.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work.

(G) Absurd dreams-Intellectual activity in dreams.

Absurdity in dreams is discussed. The frequency with which dead people appear in dreams and act and associate with us as though they were alive has produced some remarkable explanations which emphasize our lack of understanding of dreams. Often we think, what would that particular person do, think or say if he were alive. Dreams are unable to express an if of any kind except by representing the person concerned as present in some particular situation. Dreams of dead people whom the dreamer has loved raise problems in dream interpretation and these cannot always be satisfactorily solved due to the strongly marked emotional ambivalence which dominates the dreamer’s relation to the dead person. A dream is made absurd if a judgment that something is absurd is among the elements included in the dream thoughts. Absurdity is accordingly one of the methods by which the dream work represents a contradiction, besides such other methods as the reversal in the dream content of some material relation in the dream thoughts, or the exploitation of the sensation of motor inhibition. Everything that appears in dreams as the ostensible activity of the function of judgment is to be regarded, not as an intellectual achievement of the dream work, but as belonging to the material of the dream thought and as having been lifted from them into the manifest content of the dream as a readymade structure. Even the judgments, made after waking, upon a dream that has been remembered, and the feelings called up by the reproduction of such a dream form part of the latent content of the dream and are to be included in its interpretation. An act of judgment in a dream is only a repetition of some prototype in the dream thoughts.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work.

(H) Affects in dreams.

In dreams, the ideational content is not accompanied by the affective consequences that should be regarded as inevitable in waking thought. In the case of a psychical complex which has come under the influence of the censorship imposed by resistance, the affects are least influenced and can indicate how we should derive the missing thoughts. In some dreams the affect remains in contact with the ideational material which has replaced that to which the affect was originally attached, in others, the dissolution of the complex has proceeded further. The affect makes its appearance completely detached from the idea which belongs to it and is introduced at some other point in the dream, where it fits in with the new arrangement of the dream elements. If an important conclusion is drawn in the dream thoughts, the dream also contains a conclusion, but this latter conclusion may be displaced on to quite different material. Such a displacement not infrequently follows the principle of antithesis. The dream work can also turn the affects in the dream thoughts into their opposite. A dominating element in a sleeper’s mind may be constituted by a tendency to some affect and this may then have a determining influence upon his dreams. A mood of this kind may arise from his experiences or thoughts during the preceding day, or its sources may be somatic. In either case it will be accompanied by trains of thought appropriate to it.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VI: The dream-work.

(1) Secondary revision.

A majority of the critical feelings in dreams are not in fact directed against the content of the dream, but are portions of the dream thoughts which have been taken over and used to an appropriate end. The censoring agency is responsible for interpolations and additions (secondary revisions) in the dream content. The interpolations are less easily retained in the memory than genuine derivatives of the material of the dream thoughts; if the dream is to be forgotten they are the first part of it to disappear. Daytime phantasies share a large number of their properties with night dreams. Like dreams, they are wish fulfillments; like dreams, they are based to a great extent on impressions of infantile experiences; like dreams, they benefit by a certain degree of relaxation of censorship. Dream work makes use of a ready made phantasy instead of putting one together out of the material of the dream thoughts. The psychical function which carries out what is described as the secondary revision of the content of dreams is identified with the activity of our waking thought. Our waking (preconscious) thinking behaves towards any perceptual material with which it meets in just the same way as secondary revision behaves towards the content of dreams. Secondary revision is the one significant factor in the dream work which has been observed by the majority of writers on the subject.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VII: The psychology of the dream-processes.

(A) The forgetting of dreams.

The psychology of forgetting dreams is discussed. What we remember of a dream and what we exercise our interpretative arts upon has been mutilated by the untrustworthiness of our memory, which seems incapable of retaining a dream and may well have lost precisely the most important parts of its content. Our memory of dreams is not only fragmentary but positively inaccurate and falsified. The most trivial elements of a dream are indispensable to its interpretation and the work in hand is held up if attention is not paid to these elements until too late. The forgetting of dreams remains inexplicable unless the power of the psychical censorship is taken into account. The forgetting of dreams is tendentious and serves the purpose of resistance. Waking life shows an unmistakable inclination to forget any dream that has been formed in the course of the night, whether as a whole, directly after waking, or bit by bit in the course of the day. The agent chiefly responsible for this forgetting is the mental resistance to the dream which has already done what it could against it during the night. We need not suppose that every association that occurs during the work of interpretation has a place in the dream work during the night.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VII: The psychology of the dream processes.

(B) Regression.

The path leading through the preconscious to consciousness is barred to the dream thoughts during the daytime by the censorship imposed by resistance, but during the night they are able to obtain access to consciousness. In hallucinatory dreams, the excitation moves in a backward direction, instead of being transmitted towards the motor system it moves towards the sensory system and finally reaches the perceptual system. If we describe as ‘progressive’ the direction taken by psychical processes arising from the unconscious during waking life, then dreams are spoken of as having a regressive character. We call it regression when in a dream an idea is turned back into the sensory image from which it was originally derived. Regression is an effect of a resistance opposing the progress of a thought into consciousness along the normal path, and of a simultaneous attraction exercised upon the thought by the presence of memories possessing great sensory force. In the case of dreams, regression may perhaps be further facilitated by the cessation of the progressive current which streams in during the daytime from the sense organs; in other forms of regression, the absence of this accessory factor must be made up for by a greater intensity of other motives for regression. There are 3 kinds of regression: topographical regression, temporal regression, and formal regression.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VII: The psychology of the dream processes.

(C) Wish-fulfillment.

Dreams are fulfillments of wishes. There are some dreams which appear openly as wish fulfillments, and others in which the wish fulfillment is unrecognizable and often disguised. Undistorted wishful dreams are found principally in children; however, short, frankly wishful dreams seem to occur in adults as well. There are 3 possible origins for the wish. 1) It may have been aroused during the day and for external reasons may not have been satisfied. 2) It may have arisen during the day but been repudiated. 3) It may have no connection with daytime life and be one of those wishes which only emerge from the suppressed part of the mind and become active at night. Children’s dreams show that a wish that has not been dealt with during the day can act as a dream instigator. A conscious wish can only become a dream instigator if it succeeds in awakening an unconscious wish with the same tenor and in obtaining reinforcement from it. Dreaming is a piece of infantile mental life that has been superseded. Wishful impulses left over from conscious waking life must be relegated to a secondary position in respect to the formation of dreams. The unconscious wishful impulses try to make themselves effective in daytime as well, and the fact of transference, as well as the psychoses, show us that they endeavor to force their way by way of the preconscious system into consciousness and to obtain control of the power of movement. It can be asserted that a hysterical symptom develops only where the fulfilments of 2 opposing wishes, arising each from a different psychical system, are able to converge in a single expression.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VII: The psychology of the dream processes.

(D) Arousal by dreams-The function of dreams-Anxiety-dreams.

The function of dreams is discussed. The state of sleep makes the sensory surface of consciousness which is directed toward the preconscious far more insusceptible to excitation than the surface directed towards the perceptual systems. Interest on the thought processes during sleep is abandoned while unconscious wishes always remain active. There are 2 possible outcomes for any particular unconscious excitatory process: Either it may be left to itself, in which case it eventually forces its way through consciousness and finds discharge for its excitation in movement; or it may come under the influence of the preconscious, and its excitation, instead of being discharged, may be bound by the preconscious. This second alternative occurs in the process of dreaming. The cathexis from the preconscious which goes halfway to meet the dream after it has become perceptual binds the dream’s unconscious excitation and makes it powerless to act as a disturbance. The theory of anxiety dreams forms part of the psychology of the neuroses. Since neurotic anxiety arises from sexual sources Freud analyses a number of anxiety dreams in order to indicate the sexual material present in their dream thoughts.

1900

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

Chapter VII: The psychology of the dream processes.

(E) The primary and secondary processes-Repression.

The view that dreams carry on the occupations and interest of waking life has been confirmed by the discovery of concealed dream thoughts. The theory of dreams regards wishes originating in infancy as the indispensable motive force for the formation of dreams. A dream takes the place of a number of thoughts which are derived from our daily life and which form a completely logical sequence. Two fundamentally different kinds of psychical processes are concerned in the formation of dreams: One of these produces perfectly rational dream thoughts, of no less validity than normal thinking; while the other treats these thoughts in a manner which is bewildering and irrational. A normal train of thought is only submitted to abnormal psychical treatment if an unconscious wish, derived from infancy and in a state of repression, has been transferred on to it. As a result of the unpleasure principle, the first psychical system is totally incapable of bringing anything disagreeable into the context of its thoughts. It is unable to do anything but wish. The second system can only cathect an idea if it is in a position to inhibit any development of unpleasure that may proceed from it. Anything that could evade that inhibition would be inaccessible to the second system as well as to the first; for it would promptly be dropped in obedience to the unpleasure principle. Described is the psychical process of which the first system alone admits as the primary process, and the process which results from the inhibition imposed by the second system as the secondary process. The second system is obliged to correct the primary process. Among the wishful impulses derived from infancy there are some whose fulfillment would be a contradiction of the purposive ideas of secondary thinking. The fulfillment of these wishes would no longer generate an affect of pleasure but of unpleasure; and it is this transformation of affect which constitutes the essence of ‘repression.’ It is concluded that what is suppressed continues to exist in normal people as well as abnormal, and remains capable of psychical functioning.

The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901).

Editor’s introduction (1960).

Only one other of Freud’s works, the Introductory Lectures (1916 to 1917) rivals The Psychopathology of Everyday Life in the number of German editions it has passed through and the number of foreign languages into which it has been translated. In The Psychopathology of Everyday Life almost the whole of the basic explanations and theories were already present in the earliest editions; the great mass of what was added later consisted merely in extra examples and illustrations to amplify what he had already discussed. Freud first mentioned parapraxis in a letter to Fliess of August 26, 1898. The special affection with which Freud regarded parapraxes was no doubt due to the fact that they, along with dreams, were what enabled him to extend to normal mental life the discoveries he had first made in connection with neuroses.

Chapter I: The forgetting of proper names.